What the Flag Means to Me

by Earl Faubion

There are lots of flags in this world, but only one that I refer to as the flag, Old Glory herself, the colorful red, white and blue, the stars and stripes of the American flag. While growing up, my parents taught me to honor this flag, especially my dad who served in the Navy in the Pacific in WWII. I took those lessons to heart. However, it wasn’t until an unexpected little encounter with the flag at the age of 20 that defined how I’d view it for the rest of my life.

December 27, 1966, was the date, but first, let me set the background. In January 1966 I enlisted in the US Navy and went to boot camp in San Diego. After basic training, I attended electronics and sonar schools there in San Diego after which I was assigned to the destroyer USS Fletcher DD-445 which was homeported in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. In mid-October I reported on board the ship and learned she was soon leaving on a six-month western Pacific deployment which meant duty in Vietnam was a certainty.

We left Pearl Harbor on November 28th and sailed nine days to Yokosuka, Japan near Tokyo for a short stay. Then we sailed south to near Taiwan where we conducted exercises, and from there we transited west to Vietnamese waters, arriving on December 22nd. Merry Christmas!

Wow, this was going to be fun. In the shallow waters off the coast of Vietnam, the ground swell rolling in from the Gulf of Tonkin was often wicked, and that was the case on this, my first time to visit this divided country. While on naval gunfire support (NGFS) duty, the ship would slowly move parallel up and down the assigned coastline at about 5 knots or less, enough speed to maintain steerageway, thus presenting the ship’s sides to the relentless inbound waves which meant the ship was rolling constantly and violently thereby creating problems with simple tasks such as eating, walking, showering, sleeping, everything.

On December 25th we were assigned NGFS duties on the coast of South Vietnam and arrived on station on the 26th a few miles south of the DMZ. A Philippine tug on contract with the Navy had grounded on the beach, and a small group of US Marines was assisting in freeing the boat. Even though a Christmas truce was in effect until midnight, the enemy had been known to violate these truces in the past. After the tide helped refloat the tug, Fletcher was ordered south to the Cap Mia area south of Chu Lai in support of the III Marine Amphibian Force. Our target area would be near a prominent hill that stands out in Cap Mia’s otherwise flat terrain.

So here I am, a country boy who one year earlier was occupied with girlfriend problems and finishing my freshman year in college. Now, in less than two months, I’ve flown to Hawaii, sailed to Japan and through the exotic South China Sea and now find myself on the coast of the “Pearl of the Orient,” beautiful Vietnam!

Shortly before we arrived on our NGFS station, another junior sonar technician and I were told we were going to be loaned to the fire control shack where they had a personnel shortage and needed some help before the ship began NGFS duties. During NGFS watches the fire control people stood two section watches, six hours on and six hours off around the clock. Each shift needed a phone talker, someone to handle the simple task of manning a sound powered phone line that was connected to both the five-inch gun mounts and squeeze the triggers to fire the main guns. What! Fire the guns? You gotta be shittin’ me!

No, it was no joke, that’s exactly what I was assigned to do. Just simple tasks, nothing hard to learn, just pass along all orders, word for word, via the phone and on command, fire the guns remotely via a trigger built into the side of the big fire control computer after squeezing another trigger to sound an alarm in the gun mounts as a warning. Pretty heady stuff for a naïve country boy who still had the smell of boot camp and electronics schools on him. My station was a tiny corner of the fire control room crammed into a space next to the huge computer and the ship’s gyrocompass.

Each of the two triggers looked like the butt of a revolver with the barrel buried in the side of a computer. The one on the left was the alarm, squeeze it twice to warn the gun crews that the newly loaded round is about to be fired, then a second later squeeze the right trigger and feel the ship lurch as both guns salvo, sending their deadly cargo toward the target. All this was done on command of the officer in charge with a chief and several petty officers dialing in settings on the computer to aim the guns and keep them aimed as the ship pitches and rolls. The officer would issue the commands on what type of rounds to load into the guns and after confirmation was received that had been done, the command to, “shoot” would be given, and I’d squeeze the alarm, then fire the guns. After that, each mount would report to me that the bore was clear or foul.

On the 27th we went to Condition II watches, 0000-0700, 0700-1200, 1200-1700 and 1700-2400, twelve hours of watch per day. At 1145 hours on the 27th I assumed my position on the afternoon watch 15 minutes early as was the custom. Except for the sickening rolling motion due to the incessant ground swell, the watch started boringly, but soon the weapons officer perked up and said we had a mission.

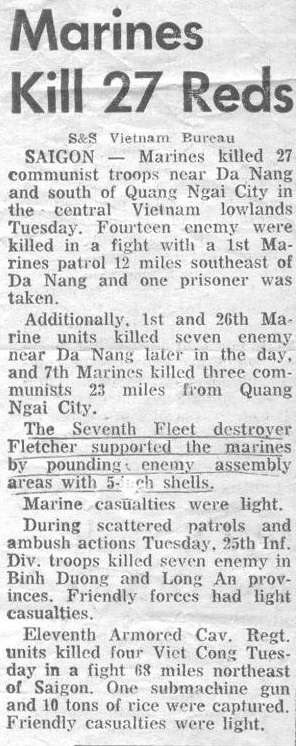

It’s been 44 years, and I don’t remember all the details. What I do remember is the orders began flowing in rapid succession as targets were located by spotters ashore, firing several rounds as quickly as they could be loaded. The officer in charge said troops were in the open and instructed the gun captains, via me on the phone, to shoot as fast as the guns could be loaded. It was hectic for a few seconds, the ship swinging wildly back and forth, the orders flying and me relaying them as fast I received them, a kind of ordered pandemonium as the guns were loaded, fired, cleared and the process repeated several times. Even below decks where we were located, we could smell cordite mixing with our tobacco smoke and the weak air conditioning that was inadequate to keep up with it all, in a small space packed with warm bodies and a monstrosity of a computer. All I remember is a flurry of orders to load HE, WP or AAC*, several “bore clear” returns from the mounts, then “loaded,” “shoot” or “cease fire.” Maybe after all these years I have some of the terminology wrong, but the wildness of the moment has stuck with me quite well. And those awful ground swells, gosh, to someone who hasn’t experienced them around the clock like that, they are hard to describe. I kept myself wedged into my corner so I wouldn’t be embarrassingly thrown to the deck.

Then it all ceased, and we all sat around silently reorganizing our thoughts. At what had we been firing? People? The officer said yes, we’d killed several enemy troops, and he congratulated us all on a job well done. Soon it was 1645 hours and the next watch began trickling in. My relief showed up, a fellow boot sonar technician who was on loan as I was. I left the space and went up to the main deck to walk aft to the compartment where my rack was. There was still time to grab a quick smoke topside and see what there was to see before going to chow.

The ship was starboard side to the coast which was about a mile or two away and clearly visible over the greenish-brown grungy rolling waves that tossed the ship about before crashing onto the sandy shore. The smell of salty air mingled with a faint suggestion of jungle rot and stack gas from our two funnels. The sun was about to set behind mostly cloudy skies, and I clung to the railing for balance and began to light up one last cigarette before going down to the mess deck. Did I forget to mention that Fletcher was the oldest destroyer in commission in the Navy at the time? She was old, but boy was she good. I love her to this day.

So there I was, bracing myself against the swell, clinging to the rail and puffing away on that final cigarette before grabbing some chow and hitting my rack early to prep for the 7-hour mid-watch and gazing at the coast wondering about the war and what our part in it had just been. Only four days earlier another destroyer, USS O'Brien DD-725 had been hit by enemy fire, and two sailors were killed, and four were wounded. She was pulled from the line and we were her replacement. We were in a hostile land. Hell, I was in a hostile land, and here I am alone for a few moments on the deck with just my thoughts.

Then I heard it, a flapping noise like laundry in the wind on a clothesline. Then it stopped, and for a minute I was puzzled, then I heard it again and realized it was coming from above. I looked up, and there she was, Old Glory flying from the mainmast, flapping violently as the ship rolled to starboard causing the mast to cut a huge arc in the sky, then going limp as the ship hovered at the end of the roll, then flapping wildly in the opposite direction as the mast swung far over to port. Back and forth went the mast, as if a giant hand was using the ship to wave the Stars and Stripes causing her to flutter madly with each wave.

The impact of that moment has never left me. Suddenly our flag took on a meaning that I never dreamed it would. A hostile land, a hostile environment, and Old Glory never looked so good. The famous photo of the flag-raising at Iwo Jima less than 22 years earlier came to mind as I was mesmerized by what I saw on USS Fletcher that evening. Now I know why all those Marines and Sailors cheered when they saw Old Glory flying on Mount Suribachi. I thought I knew the reason before, but no, I only thought I did. I had to see it in on this day before it became clear to me. Now I understand. Now I know why Francis Scott Key penned those words. Now I understand why some veterans have tears in their eyes when The Flag passes in review. Now maybe those near me will understand why I bite my lip during the playing of the National Anthem. It’s not the flag in front of me that I’m seeing, it’s that flag on Fletcher’s mast that evening on the coast of South Vietnam.

Even as I write this, I find myself trying to choke up. I’ve never been able to verbalize this experience with a straight face and only now, some 44 years later, have I gotten around to trying to put it in writing. It’s not easy. Maybe I’ve bungled the story a little, but that’s okay, it’s still my story, and it’s real. It’s in my heart forever and every time I see the Stars and Stripes I think of that afternoon so long ago. Every time! I trust that some who read this are nodding their heads in agreement because they’ve had such a moment too, a moment that lives inside them and will never die. My moment won’t die until I do.

Earl Faubion, June 14, 2010 (Flag Day)

* HE = high explosive, WP = “willy peter” or white phosphorous, AAC = “able-able-common” or anti-aircraft which, for our purposes, was set to explode at treetop level as an anti-personnel round.

The government's official Combat Naval Gunfire Support Database credits Fletcher with 15 enemies KIA for this mission.

P.S. A few years ago I was the historian for the USS Fletcher Reunion Group and one of the items passed down to me was a properly folded American flag with the simple title, “Vietnam 1966”. I knew Fletcher had been to Vietnam in January of 1966 at the end of a previous deployment as well as in December when my event occurred, so I asked the other historian if he knew which period it was from. He said he didn’t know, that he’d received the flag from the previous historian who was now deceased and no further information was available. Rather than wonder about the origin I decided to assume this flag was from December of that year which means it could be the very same flag I saw flying on the mainmast that evening in 1966. I’m hoping the members of the Reunion Group won’t mind if I ask that this flag be displayed at my funeral when the time comes. I think they’ll understand.

At 11:03 AM on September 18, 2012, this flag was flown from the USS Constitution in Boston Harbor with many Fletcher veterans and myself in attendance.

Pacific Stars & Stripes article, December 30, 1966